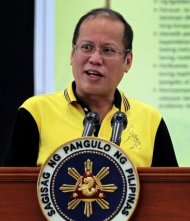

Philippine President Benigno Aquino defended a new cybercrime law Friday amid a storm of protests from critics who say it will severely curb Internet freedoms and intimidate web users into self-censorship.

Aquino specifically backed one of the most controversial elements of the law, which mandates that people who post defamatory comments online be given much longer jail sentences than those who commit libel in traditional media.

“I do not agree that it (the provision on libel) should be removed. If you say something libellous through the Internet, then it is still libellous… no matter what the format,” Aquino told reporters.

Another controversial element of the law, which went into effect on Wednesday, allows the government to monitor online activities, such as e-mail, video chats and instant messaging, without a warrant.

The government can also now close down websites it deems to be involved in criminal activities without a warrant.

Human rights groups, media organisations and web users have voiced their outrage at the law, with some saying it echoes the curbs on freedoms imposed by Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the 1970s.

Philippine social media has been alight with protests this week, while hackers have attacked government websites and 10 petitions have been filed with the Supreme Court calling for it to overturn the law.

Aquino, whose mother led the “people power” revolution that toppled Marcos from power in 1986, said he remained committed to freedom of speech.

But he said those freedoms were not unlimited.

Aquino gave a broad defence of the law, which also seeks to stamp out non-controversial cybercrimes such as fraud, identity theft, spamming and child pornography.

“The purpose of this law is to address the shortcomings of our system, so we can have a clean Internet,” he said.

US government-funded Freedom House was among the international rights watchdogs to criticise the law this week.

“Anyone who shares offending content could end up behind bars, even if he or she did not write it. Merely a Facebook ‘Like’ could be construed as libel,” it said in a statement.

“This act is a gross overreach that severely jeopardises the Philippines’ status as a country with a free Internet.”

0 comments:

Post a Comment